Prehistory

After the last ice age, the land transitioned from arctic tundra to marsh, and then a patchwork of grassland and forest. The archaeology suggests that early hunter gatherers settled on higher ground: the Surrey Hills, Caesar’s Camp at Wimbledon, and Coombe. Alternatively, navigation along the Thames resulted in settlement at places like Kingston. When agriculture arrived c. 4000 B.C., this would be on the south-facing chalk slopes that were easier to work with primitive tools. The flat Beverley Brook ‘valley’ would remain a marshy area, less appealing to those looking for pastures new. As the name suggests, beavers would have been the most likely residents.

Early days

The earliest mention of the patch is in 967, when King Edgar bestowed land by Royal Charter to a Christian named Earl Alphea. The western boundary was the Beverley Brook, and the southern Marina Avenue. The 2400 acres is about the size of the historic Parish of Merton, and the boundaries remain almost unchanged. North Surrey by this point is a landscape dotted with farmland, but our patch remains uninhabited. Instead, the 1086 Domesday Book notes multiple surrounding villages, but with few inhabitants. Their existence is likely due, not just to higher ground, but the availability of water from the chalk springs. High water flow on these rivers also permitted mills to operate.

Merton Priory and Walter de Merton: 12th and 13th centuries

The founding of Merton Priory in 1114 would have a profound effect on the area. Most of the surrounding parishes would have land under the Priory’s control, including a large part of Malden. The Parish of Morden belonged to Westminster Abbey, but an area of land called Hobalds, whose early fields would today be in Morden Cemetery, was granted to the Priory c.1225. During this period the Priory also built its ‘west barns’, to cope with the increase in agriculture. However, most of the patch would still be floodplain meadow, woods or health, and mostly common land.

In 1264, Walter de Merton, Chancellor of England, endowed the Manor of Malden to support an academic community at Oxford that would become known as Merton College. The Manor House would become the administrative centre for the management of the College and its estates. The land to the west of the patch was owned by the ‘Warden of Merton College’ until the nineteenth century. The College still owns the Manor House and has the right to appoint the vicar.

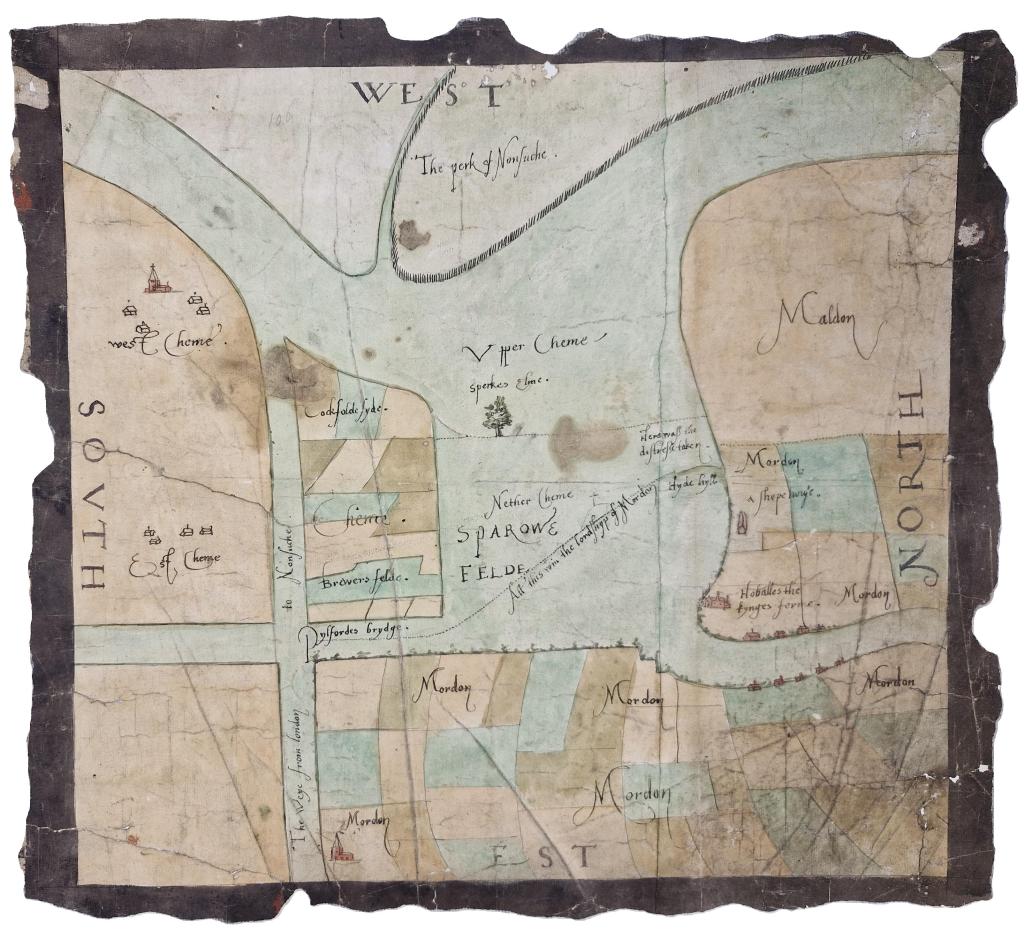

The Sparrowfeld disputes: 1280 to 1553

The expanse of common land that gives the patch its name was originally larger, providing for many commoners. By the 13th century, we know from early court documents that all was not well. As villages grew, it resulted in multiple disputes between parishes over grazing rights and firewood. The Sparrowfeld disputes would go on for nearly three centuries, during which time Henry VIII would appropriate 900 acres for his Great Park of Nonsuch, now Worcester Park. Part of the remaining land would become Cheam Common and Morden Common. The map below was drawn up to help settle a dispute between Morden and Cheam in 1553 (courtesy of the National Archives).

A shift to farming: 16th to 18th centuries

By the time Merton Priory was dissolved in 1538, and the land sold off, farms were much larger, and the West Barnes an estate. Several farms established in the area would become well known local names, including Blagdon’s, Fulbrook’s, Blue House, Mott’s Furse, and Worcester. Hobalds Farm, would expand to include Hyde Hill (the horse fields) and Merton Field (Sir Joseph Hood). Morden Common and Cheam Common would both become farmland. This shift to farming was still influenced by the landscape and soil. Much of the land would be arable, but flood prone areas were often left as meadows or used for grazing. Some fields contained furze (gorse) that could be harvested for firewood. This would often be sent to the brickworks that were opening in the area on account of the abundant clay.

The Victorian Era: railways, grand houses and the idyllic countryside

With the opening of the Wimbledon and Dorking Railway in 1857, a new type of landowner arrived: wealthy professionals, with less interest in farming, and those who could spot a business opportunity. The Garths would sell most of their land to the Hatfeilds, who would maintain the rural beauty of Morden. Charles Blake purchased much of West Barnes, and Merton College granted him a 99-year building lease at Motspur Farm to construct multiple grand houses. One of these, The Rookery, still stands inside Fulham F.C.’s training ground and is, perhaps, a nod to a bird of the period. Thomas Weeding purchased a large part of the Malden Parish.

Come out and play: Part 1

Many of the new landowners, who were absent during the week, returned at weekends to engage in their favourite pastimes, for which the area was gaining a reputation. At least six hunts or kennels were based in the surrounding parishes, and Cheam was a well-known steeplechase destination. Worcester Park Polo Club had its stables in Worcester Park, but the polo pitch was at Motspur Farm. Raynes Park Golf Course occupied most of Grand Drive, and there were are two shooting grounds in Malden. One at Blagdon’s Farm and Albermarle at Malden Green Farm. The latter is pictured below c.1925, where the Station Estate and Kingshill Nature Conservation Area currently lie (courtesy of Brian Little).

Early urbanisation on the patch: cemeteries, sewage works, and gas holders

With the new railway line, building commenced, but this was nearer the stations. A different sort of change occurred around the patch at this time. With an increase in population, 125 acres of Hobalds Farm were sold to the Battersea Burial Board in 1890, to become what was then known as Battersea New Cemetery. Wandsworth Council still owns it today. Cheam Sewage Farm would open in 1895. The Wandsworth, Wimbledon and Epsom District Gas Company (WANDGAS) would build their first gas holder in 1924. Out of sight of the early residents, nuisance industries such as pig rearing, slaughterhouses and a refuse dump would make their way to an area that would become the Garth Road Industrial Estate.

Full speed ahead

Real change began in 1925, due to the electrification of the railway line and the construction of Motspur Park Station. The first area to be developed was West Barnes. Sidney Parkes was living at the renamed Motspur Park (previously Farm) but would also purchase Blagdon and Blue House farms. First, he financed the building of the railway station, which he named after his estate. He would then go on to develop a large part of the area, naming some of its famous roads after his children. Most of the neighbourhoods that surround the patch were built later, with the Station Estate completed in 1935. The full extent of urbanisation can be seen in the comparison below. These maps, however, only tell part of the story.

Come out and play: Part 2

While it looks like there are still a few fields dotted around, the reality is that by the 1930s all the farmland had disappeared . Instead, the white patches are mostly playing fields. South-west London had become a prime destination for employers, schools, and other organisations, looking to provide their members with sporting facilities. Some of these playing fields would soon play a very different role in the history of the area.

‘Dig for Victory’

The Second World War would see huge amounts of land turned over to allotments. Larger playing fields did not remain as grass but were instead used to grow cereal crops. Many allotments would continue until rationing ended in 1954, and in some cases into the 1970s. Two allotment sites remain to this day.

Late twentieth century

After the war the final pieces of the patch jigsaw started to come together. An area used to store rubble from bombed buildings, would be covered in soil and grass and is to this day called ‘The Dump’ by locals. In 1947 Merton and Morden and Carshalton councils completed what is today Merton and Sutton Joint Cemetery. Green Lane Primary School opened in 1950, and Cheam Sewage Farm would be upgraded and enlarged to become Worcester Park Sewage Works in 1955.

The 1970s would see the end many wartime allotments: Arthur Road nursery (Thompson’s Plants); the paddock (Lower Morden Equestrian Centre); Kingshill Nature Conservation Area after trees naturally took over neglected plots, and an enlarged sewage works. One major change, generally, was a loss of grassland. Sir Joseph Hood was narrowed to make way for the plant nursery, and scrub took over grass verges that lined Green Lane. Another change occurred in 1971 when Dutch elm disease reached the area. Many lanes had been lined with them, and some tree stumps are still visible on ‘Pig Farm Alley’ between the Mayflower Park wetlands and the paddock.

The modern era

The early twenty-first century would bring about two major developments. Firstly, The Hamptons and Mayflower Park would replace Worcester Park Sewage Works. Within this estate there are a Roman amphitheatre and a wetland with reedbeds. The latter is actually ‘SUDs’ (sustainable drainage systems), that stores and filters road run-off so as not to overwhelm the sewer system. Secondly, Sir Joseph Hood Memorial Wood would be enlarged by the addition of Millennium Wood, or ‘Jubilee Clump’ as it often gets called.